I have been to Dixon's many times, I always look at the used 19th century smooth bores. The muzzle ends of their barrels look almost thin enough to shave with. Can anyone explain why with the modern and stronger steels we have today the smoothbore barrels of to day are so heavy compared to those of long ago?

-

This community needs YOUR help today. We rely 100% on Supporting Memberships to fund our efforts. With the ever increasing fees of everything, we need help. We need more Supporting Members, today. Please invest back into this community. I will ship a few decals too in addition to all the account perks you get.

Sign up here: https://www.muzzleloadingforum.com/account/upgrades -

Friends, our 2nd Amendment rights are always under attack and the NRA has been a constant for decades in helping fight that fight.

We have partnered with the NRA to offer you a discount on membership and Muzzleloading Forum gets a small percentage too of each membership, so you are supporting both the NRA and us.

Use this link to sign up please; https://membership.nra.org/recruiters/join/XR045103

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

barrel thickness

- Thread starter bud in pa

- Start date

Help Support Muzzleloading Forum:

This site may earn a commission from merchant affiliate

links, including eBay, Amazon, and others.

rich pierce

70 Cal.

1) It’s easier to turn barrels to a thicker wall. Easier is cheaper. 2) Concerns over liability with non-barrel steels. 3) Limited demand for actual shotguns (shooting shot) where a light muzzle matters.

Rice is now making a 4140 barrel steel thin walled fowling barrel. It’s more expensive.

Rice is now making a 4140 barrel steel thin walled fowling barrel. It’s more expensive.

plmeek

40 Cal.

I agree with Rich. Modern barrels are turned on a lathe. The thinner the barrel wall, the lighter the cut that can be made and more time required turning the barrel.

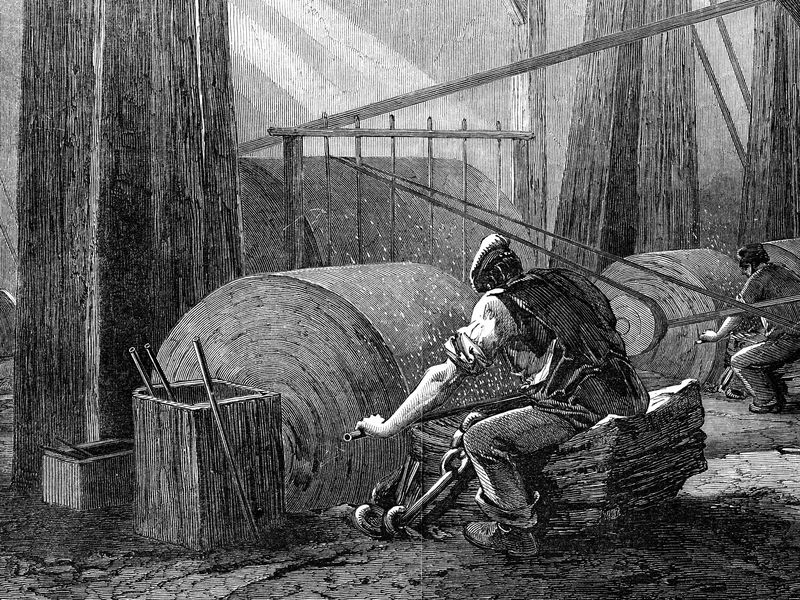

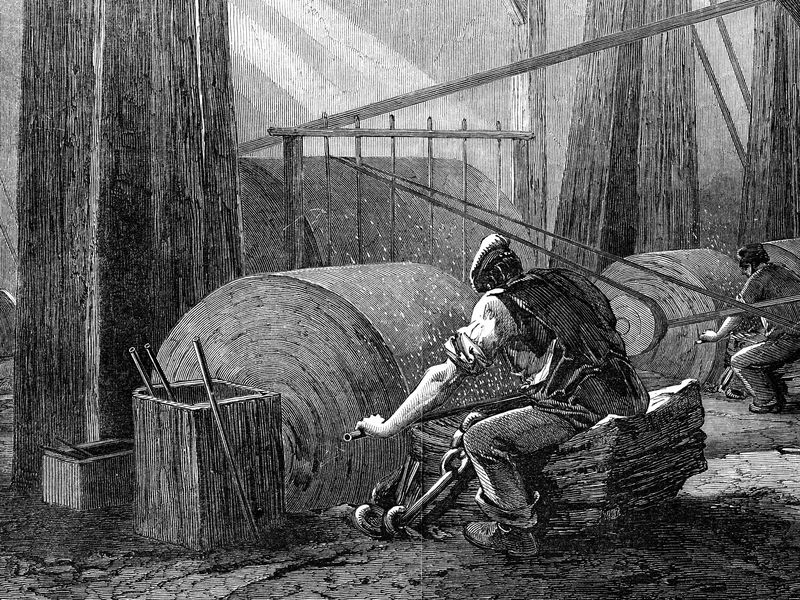

In the old days, they didn't use lathes. They ground the barrels on large grinding stones as shown in this 18th century woodcut. They could grind the barrel as thin as desired with a lot less stress on the metal.

In the old days, they didn't use lathes. They ground the barrels on large grinding stones as shown in this 18th century woodcut. They could grind the barrel as thin as desired with a lot less stress on the metal.

Thanks for the replies.

1) It’s easier to turn barrels to a thicker wall. Easier is cheaper. 2) Concerns over liability with non-barrel steels. 3) Limited demand for actual shotguns (shooting shot) where a light muzzle matters.

Rice is now making a 4140 barrel steel thin walled fowling barrel. It’s more expensive.

IMHO #2 reason is really #1 Liability the big killer of everything today.

---------In the old days, they didn't use lathes. They ground the barrels on large grinding stones as shown in this 18th century woodcut. They could grind the barrel as thin as desired with a lot less stress on the metal.

Disagree completely on this one. Grinding as shown, with such a wide wheel would put tremendous strain on a barrel. They would also have zero ability to insure consistent barrel wall thickness from both end to end, but more importantly having an even wall thickness around the circumference.

I don't know how the various companies are doing it today, but I do know I can setup a metal lathe with proper tooling geometry to put very little cutting stresses.

Capt. Jas.

58 Cal.

- Joined

- Aug 19, 2005

- Messages

- 3,005

- Reaction score

- 1,248

To add to what Rich posted about deflection and liability....most shoot ball out of their guns these days so a thicker wall is not really a big deal to most. Also many barrels are turned on the same OD and have different bore sizes these days. Ex, Colerain "Griffin" 20 and 16 is the same size on the outside. Another factor with some original fowling barrels (as opposed to fuzee types) was that the muzzle area was relieved within the bore. Many original fowling barrels also had much larger breeches than the standards produced these days. For example, the breech on the original barrel that Rice is replicating in 4140 is actually much larger than the repop.

plmeek

40 Cal.

Disagree completely on this one. Grinding as shown, with such a wide wheel would put tremendous strain on a barrel. They would also have zero ability to insure consistent barrel wall thickness from both end to end, but more importantly having an even wall thickness around the circumference.

I don't know how the various companies are doing it today, but I do know I can setup a metal lathe with proper tooling geometry to put very little cutting stresses.

I don't think I expressed myself very well. I was trying to support Rich Pierce where he said, "It’s easier to turn barrels to a thicker wall. Easier is cheaper."

I could have used a better term than "stress" to make my point about turning a thin walled barrel on a lathe. The cutting tool on a lathe is a single point that puts pressure on the work. If the work is a solid bar, this pressure causes a small amount of deflection in the bar. If the work is a thin walled tube like a barrel, the deflection is more significant.

On a cylindrical tube or straight wall tube, a follower rest can be used to support the tube on the opposite side from the cutting tool. But for a tapered barrel, a traditional follower rest doesn't work because the diameter of the barrel changes along its length. One would have to use a steady rest and reposition it a time or two to turn the tapered barrel to the desired conditions. Or one would need to take a lot of light cuts on the barrel without any rests in order to minimize the deflection of the barrel.

Either approach would take more time and add to the costs of the barrel. You can order a thin walled fowler barrel from some custom barrel makers, but it will cost more than the standard barrel from Colerain or Rice.

As far as grinding barrels, that's the way it was done. The woodcut I posted was from a broadsheet article published in 1851 in the Illustrated London News.

I would agree that it probably lacked the precision we expect today, but it was no more or no less as precise as the rest of the processes in making a barrel in the 18th and first half 19th centuries. After all, a barrel started out as iron skelps that were forge welded around a mandrel. It was then reamed out (it was called boring in the day) to proper bore size. The barrel would be straightened by eye, looking down the bore. The large barrel manufactures then ground the external profile either round or octagon or combination. Small shops would have hand filed the external profile.

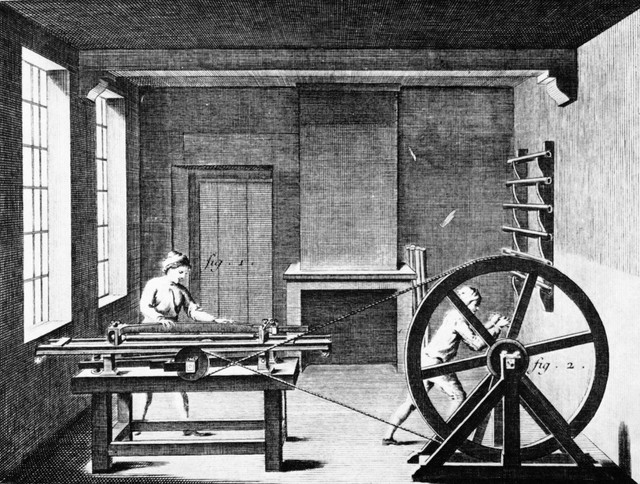

Here is another image showing a method of grinding a barrel in France in the 1700's. Since it isn't using water power, this likely is a method used before the Industrial Revolution.

hanshi

Cannon

Don't know if it's done differently nowadays, but even two or three decades ago modern gun manufacturers had their barrels eyeballed for straightness.

This is how Pedersoli does it:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4VeZynGoIQo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4VeZynGoIQo

Similar threads

- Replies

- 88

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 45

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 559